The coach behind the champions

Ahead of the IPC Athletics Grand Prix in Brisbane, world renowned para-athletics coach Iryna Dvoskina gives an insight into how she gets the best out of her athletes. 04 Mar 2015

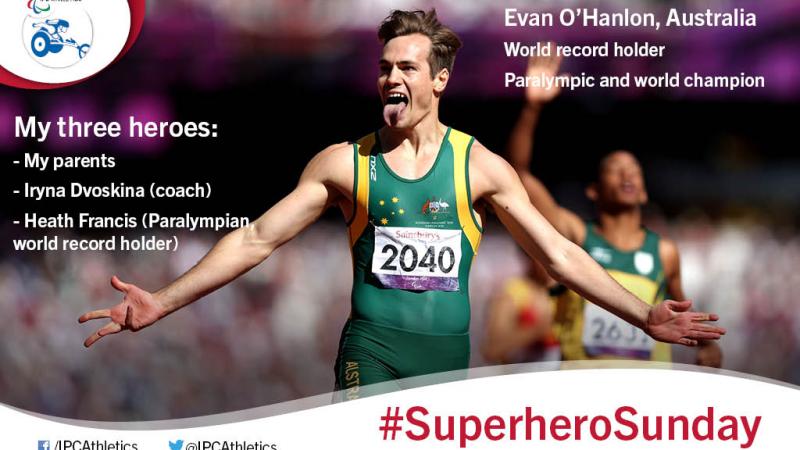

Para-athletics coach Iryna Dvoskina with Paralympic and world T38 sprint champion Evan O’Hanlon.

“I still have a Ukrainian mindset, I’m not Australian. Australians are really relaxed laid back people. I’m really strict. And all my athletes behave like Ukrainians!”

The saying ‘behind every great man there’s a great woman’ could not be more true when it comes to many of Australia’s celebrated para-athletes.

Iryna Dvoskina has been successfully coaching talented Paralympic track stars for over 20 years, both in her home country Ukraine, and for the last decade at the Australian Institute of Sport in Canberra.

The 56-year-old has some of the country’s finest para-athletics talent under her wing including Paralympic and world T38 sprint champion Evan O’Hanlon and Scott Reardon, the 100m T42 world champion.

So she is ideally placed to underline the importance of the IPC Athletics Grand Prix in Brisbane next week (6-8 March) – the first IPC Athletics Grand Prix to take place in the country.

“It’s really important that we have an IPC Grand Prix here, now. Athletics isn’t a game – it can be a boring sport with a lot of routine,” she said. “If we have a major international competition here, kids can see it’s real – it will attract more kids and international athletes as well.”

Dvoskina’s track record speaks for itself. Paralympic and world champions, world gold medallists, and world record holders past and present have all trained under her guidance, including T47 sprinter Heath Francis and T47 high jumper Aaron Chatman.

Her unique take on coaching is perhaps one of the keys to her tremendous success.

“A lot of coaches who are coaching disabled athletes think that technology is key,” she explained. “I think differently: body is key. Athletes need to train their body to use technology.”

After obtaining University degrees in physiology and coaching, Dvroskina was lecturing in Ukraine when she was approached to develop a Paralympic programme. As her interest grew, so the foundations for her coaching systems were born.

“All my experience, knowledge and education came from a really strong Soviet Union system - the system I grew up with,” she explained.

Then in 2003, after 10 years coaching the Ukrainian athletics Paralympic team, Dvoskina decided to follow her mother - also a renowned athletics coach - and move to Australia.

Coaching is certainly a family affair. Married to Yuriy Vdovychenko, the former head coach of the Ukrainian Paralympic swimming team and now a central figure in Australian swimming at the country’s National High Performance centre, the pair are used to discussing their charges round the dinner table.

“Of course we have our own time,” she explained. “But if we are talking about athletes it’s not upsetting him or me. It’s our job and our life.”

Meanwhile Fira, Dvoskina’s 82-year-old mother, is a regular coach at her base in Sydney, attending track sessions three times a week.

Dvoskina however has already asked O’Hanlon to let her know when it is time for her to call it a day, especially after recalling a training session where her mother were at the track:

“I was looking after her all the time, putting a chair in the shade, because she is 82! I don’t want anybody looking after me at the track and finding me chairs in the shade. I said to Evan, when I start to look funny, like my mum, you need to tell me to stop.”

It is no wonder Dvoskina has developed such a close bond with her athletes. Spending up to six hours a day, six days a week in each other’s company on the track and in the gym, she knows exactly what makes each individual tick.

“I treat them like my own kids. Parents are usually strict to their own kids; we have to be strict. But we love our kids, we want the best for them. I love all of them like my own children. If I’m not strong, they never will be either,” she explained.

And the results are evident for all to see.

Double world and Paralympic champion O’Hanlon has been working with Dvoskina for 10 years, and like Reardon, regards her as a ‘second mum’. Visually impaired sprinter Chad Perris topped the world rankings in the 100m T13 last year with a personal best of 10.97, while Sam Harding, 2009 Paralympic Youth Games triple gold medallist, shows great promise in the T 13 middle distances.

Reardon, who dead-heated with Germany’s Heinrich Popow, to win world gold in 2013 explained:

“She has the unique ability to make any athlete race to their full potential. She cares about absolutely everything and it’s not just about the running, it’s about every aspect of my life. The knowledge she has is second to none. She’s the reason I run fast, there is no question about that.”

But maybe there is a simple answer to why Dvoskina gets results.

“I’m just making them Ukrainian”, she laughed.

“I still have a Ukrainian mindset, I’m not Australian. Australians are really relaxed laid back people. I’m really strict. And all my athletes behave like Ukrainians!”

Around 125 athletes from six countries will take part in the second IPC Athletics Grand Prix of 2015, the first time such an event has been held in the Southern hemisphere.

Facebook

Facebook

Instagram

Instagram

Twitter

Twitter

Youtube

Youtube