'Forza', Alex

For him, who has become a symbol of struggle in the face of life's fragility, the word 'pity' has no place 24 Jun 2020

At the entrance to the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games Athletes' Village was a huge bronze statue of Icarus, decorating the flag square. It would have been more appropriate, perhaps, to choose a sculpture of the powerful Hercules or the brave Achilles, for example, to represent the values that every athlete should remember on the way to their final competition. But the Brits chose Icarus. Why? There's no reference to the guy being particularly athletic. He didn't beat any Minotaur or cut off the head of any Medusa. If anything, he is judged to have been reckless in flying too close to the sun with his wings stuck together with a melting wax, after which he fell into the sea, dead. So why that symbol, in that place, at that time?

High-performance athletes are very particular characters. They inspire us because their stories are built from archetypes that we connect with at a very deep level because they represent the 'must be' of life. They are born into an environment that has nothing particularly special, they accept the call to adventure, they receive the help of a mentor or talisman, they make a major sacrifice, they win and they come back with something more transcendent.

This is more or less how the story of James (Rodriguez), Nairo (Quintana), Martina Navratilova or Muhammad Ali can be told, and they resonate emotionally in all of us because they are the same steps we must follow if we are to give purpose to our own lives. Like art, they manage to connect us with some mystical energy that cannot be explained in words.

Now, within the universe of stories are those of athletes with disabilities. They inspire even more because, from the cultural construction in which we live, their sacrifice is superior. In the 'normal' West, it is still true that not being able to see, having Down's syndrome or being in a wheelchair are characteristics of the 'other' who is undesirable and can hardly be related to sporting excellence. That's why they are more heroic stories: besides beating their rivals, they must also overcome barriers in their environment and attitudes. That does not mean that the role of people with disabilities, in general, is to inspire people without disabilities. But, individually, there are many extraordinary and fascinating stories.

And that is why the Paralympic Games, where they are made, are such a powerful tool for social transformation. Equivalent to the 'gay parade', it is a space where diversity is celebrated, exhibited without any complex and put in the face of a world that does not like to look at what it does not understand. There is nothing like sport to bring into the spotlight the particularities of functionality. "Look at what I am and look at what I can do. Get used to it."

Now, within the universe of Paralympic athlete stories is the story of Alex Zanardi.

He was a F1 race driver. Years later, he had a devastating accident during a competition at Lausitzring in Germany. After a long rehabilitation process, he walked out of the hospital with prosthetic legs, returned to the same track where he had crashed and finished the remaining laps. A symbolic victory. But the thirst for real victories kept burning inside him and that's why he learned to use a handbicycle.

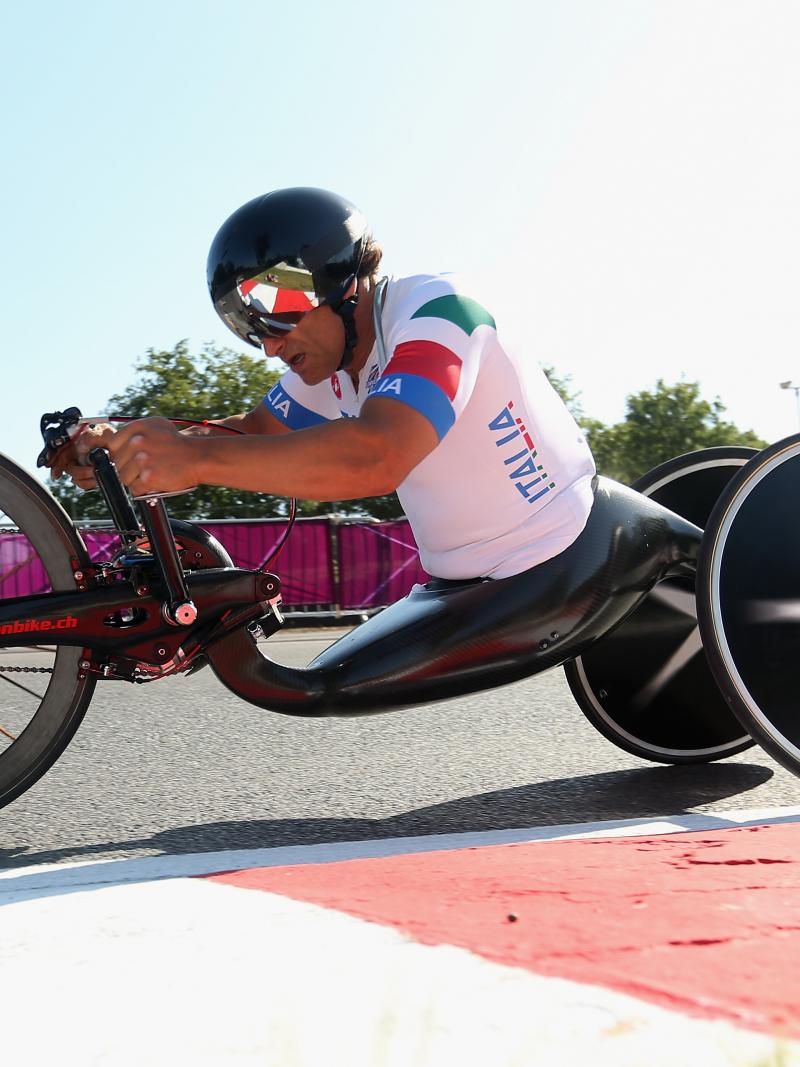

He trained more and better than the others, he put up with the pain in his arms and the blisters on his hands and after a while, he achieved the honour of being called up to the team that would represent Italy at London 2012. He knew very well what he wanted, and the execution of the tests was impeccable. He won two gold medals, one in the time trial and one on the road.

You have to see the face he made on the podium while the Italian anthem was being played, which he made everyone listen to, thanks to his determination and his work well done. Anyone would feel that his debts to life would be paid at that moment. In his own way, he had left behind a very difficult moment in his life, he was someone else. But Alex is not just anyone.

The intimate company of suffering that any performance cyclist undergoes was already part of his routine and that's why he returned to compete in Rio 2016 and won a gold medal in the time trial and a silver medal in the peloton race, just on the 15th anniversary of his accident at Lausitzring. Anyone would stop there and feel that it was more than enough. But Alex isn't just anyone.

His thirst continued and at 53, he set his sights on the Tokyo 2020 Paralympic Games. He probably thought he had one last bullet left. The pandemic postponed the event to next year, but he decided not to waste any time and continued training. On Friday afternoon, during a preparation competition, he was going down a hill and was thrown by a truck that was coming up.

"All the numbers are fine, but neurologically it is not possible to make an evaluation," said Dr. Oliveri, who operated on the Paralympic champion. "I'm treating him because he's worth treating, being optimistic or not is useless at this point. What if he has permanent damage? These are hypotheses that don't make sense, we can't know what the prognosis will be tomorrow, in a week or two.”

Some versions say he invaded the lane. Others, that the race did not meet basic standards of road safety. The truth is that today, once again, Alex is torn between life and death in an ICU. I feel sorry for his family, for the people whose lives he touched and for the entire Paralympic Movement. But for him, shouldering all the uncertainty of the world at this moment; becoming a symbol of struggle in the face of the fragility of life; a prophet with actions that show a path towards transcendence; for him, ephemeral but enormous, the word 'pity' simply does not fit.

I remembered this morning the poem that was written on the pedestal of the Icarus statue in London:

My Audacity Was My Joy,

Not My Disaster,

I reached A Glory Higher Than Olympus,

My Fall Was Worth The Flight.

Juan Pablo Salazar

Facebook

Facebook

Instagram

Instagram

Twitter

Twitter

Youtube

Youtube

TikTok

TikTok

Newsletter Subscribe

Newsletter Subscribe