Brazilian sport fans learn to love goalball in silence

Traditionally some of the noisiest spectators, Brazilians at Rio 2016 have quickly learned that goalball players need to perform in silence. 09 Sep 2016

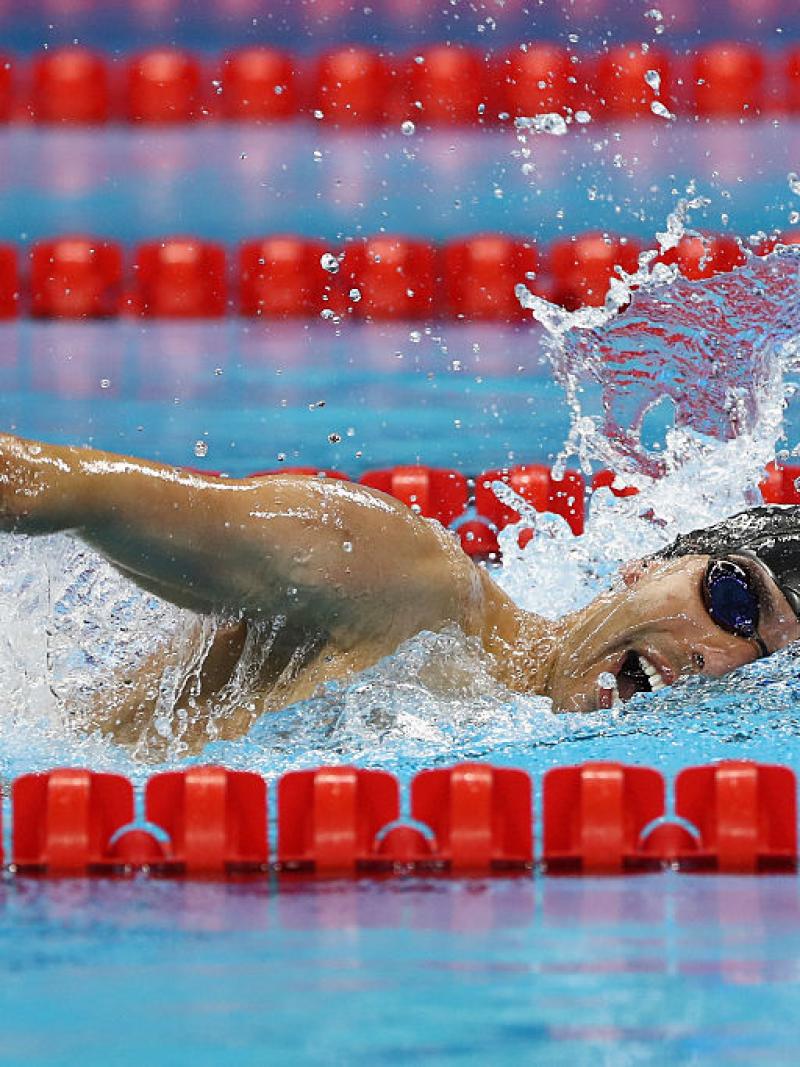

Brazil's team saves the ball during their Goalball Women's Preliminary Group C match against the United States of America at Future Arena.

Put Brazilian fans into a stadium where their national team is playing and in most ordinary sports you can be guaranteed a carnival atmosphere, a colourful crowd and non-stop cheering and jeering.

But goalball isn't an ordinary sport.

Developed after the Second World War for injured armed services personnel, goalball is played by visually impaired athletes in complete silence so that they can hear special bells in the ball and listen to the instructions of officials.

At the Rio 2016 Future Arena, Brazilians have embraced the sport with all their traditional love for ball games. But they have learned to do so in silence.

“Staying silent is a question of respect for the athletes,” said Jayme Marques, a Rio de Janeiro local enjoying his very first goalball game.

Silence when the ball is in play does not mean that goalball spectators cannot cheer when a goal is scored. And the Brazilians had plenty of reasons to cheer: the men’s team kicked off proceedings on Thursday with a tense 9-6 defeat of Sweden.

The victory of the Brazilian women was even more emphatic: Brazil beat the USA 7-3, with 18-year-old Victoria Amorim scoring six goals in the opening match.

“I was surprised by the fans, it was impressive,” Amorim said after the game. “They were really quiet at some times.”

Brazilian spectators appreciated the performance of their national teams and rose as one to applaud their efforts.

“Watching the game, I had the sensation that they could see,” said Khalil Abdala, one of a group of friends who had come to Rio from São Paulo to enjoy the Paralympic Games and watch goalball for the first time.

“They're very sensitive,” Juliana Dermendjian said. “I would like to try it one day.”

Facebook

Facebook

Instagram

Instagram

Twitter

Twitter

Youtube

Youtube

TikTok

TikTok

Newsletter Subscribe

Newsletter Subscribe