Tokyo 2020: Yutaka Nakamura’s legacy

How one man started the Paralympic Movement in Japan 23 May 2019

"Japan has become a mature society and must become a force that drives progress even further."

Dr. Yutaka Nakamura, an orthopaedic surgeon, was one of the most instrumental people in bringing the 1964 Paralympic Games to his home country in Japan. What the Oita native did not know is how far legacy would impact, especially with Tokyo 2020 set to take place.

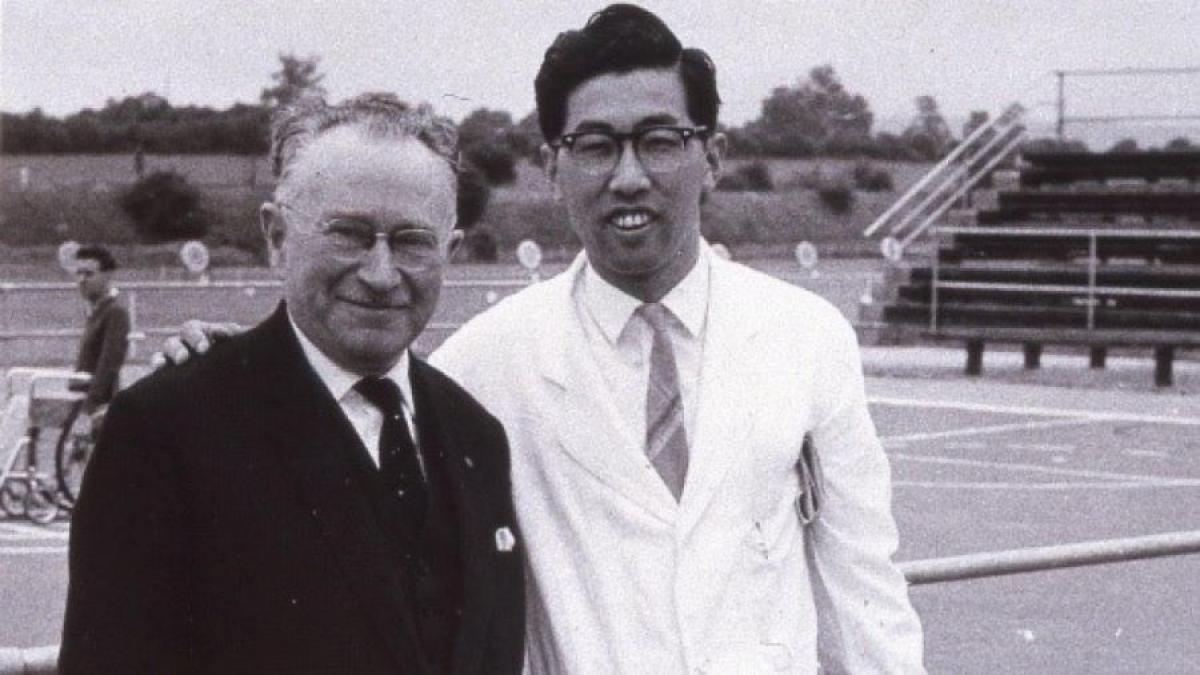

Nakamura travelled to Great Britain in 1960 to study with the man known as the “father of the Paralympic Games”, Sir Ludwig Guttmann, who was incorporating sports in his rehabilitation treatments for patients with spinal cord injuries.

In Japan, the concept of rehabilitation had not yet become widespread, and Guttmann’s unprecedent approach caught Nakamura’s interest.

He returned home determined to put what he had learned into practice, immediately organising Japan's first full-scale athletic competition for people with impairments: The First Oita Prefecture Para Sports Tournament.

However, it was a time in Japan when treatment was still focused on immobilisation and bed rest. Nakamura's idea of having patients participate in sports was met with heavy criticism.

Fighting the criticism

“People told him it was cruel to ‘put people with impairments on display’ that was ‘the same as showing them off like in a circus', and that he was trying to ’undo all the rehabilitative work that had been achieved' by having patients participate in sports,” said Nakamura’s eldest son Taro, who is also a physician.

Despite the harsh criticism, Yutaka Nakamura set a personal mission to bring the Paralympic Games to Tokyo.

He made the rounds of the relevant government offices. But officials repeatedly insisted that Japan was far from ready to host the Paralympic Games.

That did not discourage Nakamura.

In 1962, he used his own money to send two Para athletes from his Oita hospital to Great Britain to participate in the Stoke Mandeville Games. News that the first participants had arrived all the way from Japan electrified the British media, eventually spreading to the global press.

It was exactly what Dr Nakamura had hoped.

The Japanese media, which until then had shown little interest in the story, ran it everywhere as soon as the international news broke. For the Japanese public, Para sports was finally on the map.

In 1963, the following year, Nakamura's tireless efforts led to official approval for the Paralympic Games to be held in Tokyo. With government backing in hand and grassroots support taking care of the difficult financial hurdles previously in place, Nakamura's dream finally became a reality. The Paralympic Games would follow the Olympic Games as a historic national event.

Small victory, bigger battle

Nakamura continued to pour himself into Para sports even after the Tokyo 1964 Paralympic Games. His life's mission was to see people with impairments integrated seamlessly into society--not just in Japan but all over the world and especially in developing countries--to the point that the term “people with impairments” disappeared entirely.

Driven by these convictions, Nakamura based his efforts out of Oita Prefecture.

In 1975, the first Far East and South Pacific Games for the Disabled (FESPIC) was held in Oita. A total of 973 athletes from 18 Asian and Pacific countries, including Japan, participated in the event.

Nakamura wanted to create a sporting event in which athletes from developing countries, where Para sports had not yet taken hold, could participate – as these countries were facing the same disadvantages versus the West that Japan had experienced prior to the Paralympic Games.

He worked together with like-minded people in Australia, Singapore, Hong Kong, and elsewhere, ultimately persuading key players in those various countries as well as companies in Japan to support the effort.

Then, in 1981, Oita became the site of the world's first wheelchair marathon. The leading advocate for this momentous event was Nakamura.

In 1984, three years after the first Oita International Wheelchair Marathon, Nakamura passed away at the age of 57. The facilities he established and the sporting events he founded have continued to develop to this day, so that even in the 21st century his legacy is still evolving on a global scale.

South African athlete Pieter du Preez competed at the wheelchair marathon event in the T51 class in 2017 and won his third consecutive race.

“I’ve been to all sorts of countries, but I can say that Oita is the most inclusive place I’ve ever been to,” Du Preez said.

“There are flat surfaces everywhere you go to accommodate wheelchairs and considerations for other types of impairments too, like textured paving blocks all around the city for people with visual impairments. As someone who uses a wheelchair, I was quite impressed with this city.”

Legacy lives on

When the Tokyo 1964 Paralympic Games were held, about 30 per cent of people with physical impairments were aged 65 or older. The aging of Japan has since progressed, and that proportion has now grown to over 70 per cent [74 per cent as of April 2018 according to the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare].

The proportion of people with physical impairments tends to increase with age, and it is expected to continue increasing as the population continues aging. As this happens, striving for a society that accepts diversity—the aim of Para sports—will become even more important.

“The Paralympic Games are back, over half a century after the Tokyo 1964 Games. Japan has become a mature society and must become a force that drives progress even further,” Tokyo 2020 spokesperson Masa Takaya said.

“Fostering not only universal design, but also a barrier-free mentality, and having as many people as possible learn through the Games to appreciate all sorts of differences including in abilities and to accept diversity,” Takaya added.

Facebook

Facebook

Instagram

Instagram

Twitter

Twitter

Youtube

Youtube