Antonios Tsapatakis soul-searching for Paralympic gold

'If I had to choose either the gold medal or to stand up again, I would choose the first,' says Greek Para swimming champion 09 Oct 2020

If given the choice, Antonios Tsapatakis says he would rather win a Paralympic gold medal than be able to walk again.

For the Greek Para swimming champion it would mean he had finally achieved his dream for himself and others.

As an acclaimed motivational speaker on disability and equality, he would use the gold medal to inspire others to go for their goals no matter how hard-won.

The postponed Paralympics in Tokyo next year will be the third time of trying for Tsapatakis. In London 2012 and again in Rio 2016 he narrowly missed out on a medal in the 100m breaststroke SB4.

“It is my dream to win gold,” he said. “I didn’t win in both Paralympics but this just motivates me to do better.

“If I had to choose either the gold medal or to stand up again, I would choose the first one. I think the gold medal would make my soul stronger and taller. I can also use it to help other people stand again from their soul.”

Tsapatakis describes his “soul” as his powerful inner spirit, which is boundless and free from physical limitations.

“You can’t cut the soul into pieces,” he explained. “I connect with my mind and my soul. My body can’t work but my mind says, ‘Antonios, you can do it. You can do it in a different way.’”

The day life changed

In 2006 the 32-year-old lost the use of his legs in a motorcycle accident outside the swimming pool where he learned to swim aged five and regularly trained as a water polo player.

It is near the family home, which he shares with his parents and younger brother in Chania, Crete. He was 19 and 1.88m and in an instant his life had changed.

“I have asked myself, why did that problem choose me? But every bad situation that I have had in my life, I take the view that I will get past it. It trains me to be better and more powerful,” Tsapatakis said.

Just months later, he went back to the pool for a swim which, he said, “helped me to live”.

Tsapatakis has always had an affinity with water and the healing powers on his body and soul: “It makes me feel alive and free.”

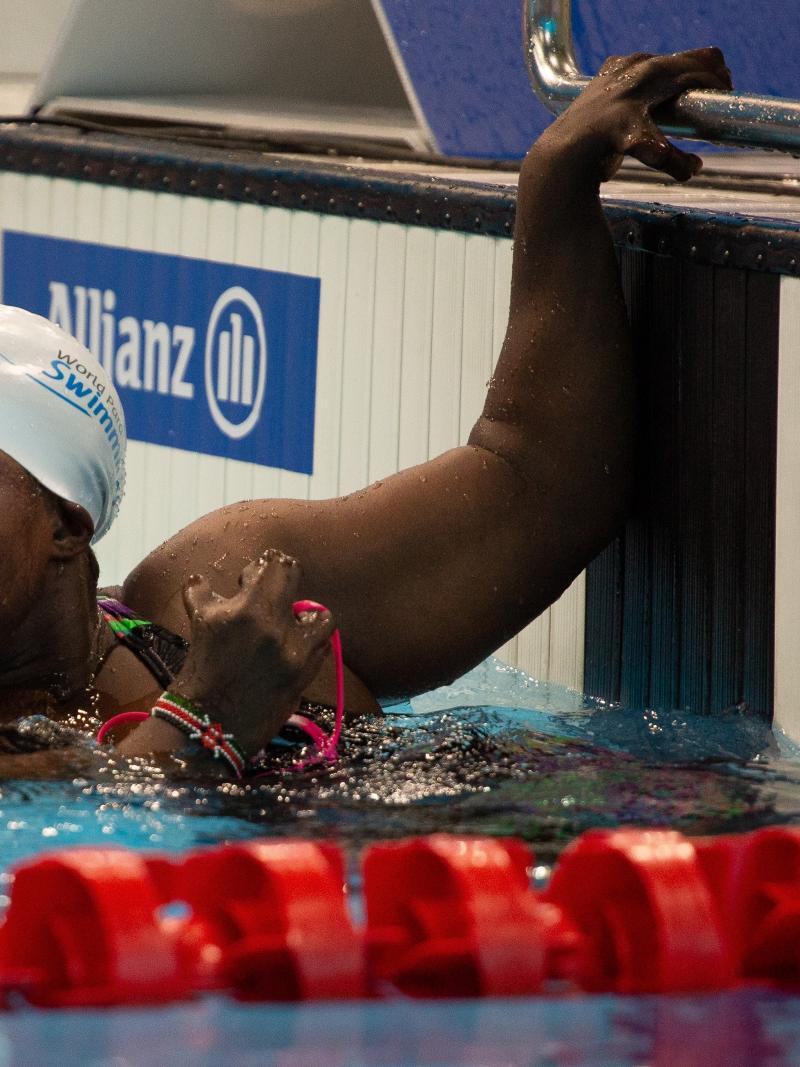

To illustrate this, in 2017 he posed for underwater images for Greek photographer Nicholas Samaras. The photographs, which went viral on the internet, show him standing in front of his wheelchair. The idea was to reflect the freedom he feels in the water and how he is winning in the pool and in life.

“In the caption under the photographs I thank the water and the swimming pool,” he said.

“The pool made me a man and helped me to cope with what it is to lose and win. The street outside took my ability to walk but I kept on training inside the pool and that gave me the ability to help myself and inspire others, and that is more important to me than standing and walking.”

Tsapatakis made his international debut in 2009 at the European Championships in Reykjavik, Iceland, where he won bronze in the 100m breaststroke.

He has since competed and won medals at many other events, including the 2015 World Championships in Glasgow, Great Britain, where he won silver in the 100m breaststroke final and broke the European record.

He trains six days a week, including during the lockdown when public pools were closed. His trainers, Chrysafis Vangelakakis, who is based near his work and apartment in Thessaloniki, and Ioannis Natsios in Megalonisos, near his family home, both have their own private pools where he can swim alone.

Fighting for equality

Tsapatakis’ determination to win in the pool has been matched by his dedication to fighting discrimination against persons with disabilities.

The popular athlete, who has more than 100,000 social media followers, spent 11 years campaigning to get the law changed in Greece to allow people with disabilities to work in the police.

At the time of his accident he was a student at the Hellenic Police Academy, but he was forced to leave. He later discovered 13 other officers also had to quit due to their disability.

With no support from politicians, he contacted the Prime Minister’s office and used his name as a Para swimming champion to get attention, and he succeeded.

Hours after his disappointing 100m breaststroke final in Rio, he heard the news that the law would be changed.

“I was very proud of that,” he said. “It felt like standing up in first place on the podium and hearing my national anthem. It was like winning the gold medal.

“It meant we could finally go back to work and earn a salary. It also enabled other disabled people to dream of having a job in the police.”

He now works in the traffic division educating adults and children about road safety.

“I do a very important job,” he said. “If I had had this kind of education when I was at school, then I may not have had my accident.”

Tsapatakis admits he was going too fast when he was thrown from the motorcycle. He also campaigns to stop people illegally parking in disabled bays and teaches water safety and conservation.

Alongside his police job and competing, Tsapatakis is building up a career as a motivational speaker on disability, equality and Para sports.

“As a Paralympian I can educate people. When I go to schools to give speeches, children ask, ‘How can you swim?’ And I tell them I swim with my hands and show videos of my races.”

In 2016 he co-authored a children’s book, called ‘To oneiro’ or ‘The Dream’ with Elena Thoidou, the wife of his trainer Natsios.

The aim of the book about a disabled boy called Toni, which is part autobiographical and part fiction, was to teach children and their parents that all people are equal.

They are currently writing another book about Toni as a 16-year-old, which will be published after the Paralympics next year. The story will tackle the issues of disability and falling in love.

“It is important to learn that love from the soul has no boundaries, whether you are disabled or not.”

As Tsapatakis dreams of a gold medal in Tokyo, he urges people not to let boundaries or limiting beliefs stop them, too: “If you have a goal, just go for it, nothing or no-one can stop you. This is freedom… willing it makes you free.”

Facebook

Facebook

Instagram

Instagram

Twitter

Twitter

Youtube

Youtube

Tiktok

Tiktok