Amazing adventures of Norway legend Pedersen

From Antarctica to Everest, seven-time Paralympian has always liked a challenge 13 Feb 2022

Not many people have walked to the South Pole and climbed Mount Everest. Norwegian Paralympian Cato Zahl Pedersen has.

While he has won 13 Paralympic gold medals across summer and winter Games, has enjoyed his stint on a reality television dancing show and has a rehab centre named after him.

“The South Pole was the bigger challenge," said Pedersen, who lost both arms following an accident at a young age.

“I climbed Everest but the last day we turned 200m below the summit because of expected weather conditions and too many people in the mountain. That was 8,650m and I am quite satisfied with that.

“The South Pole is tricky. You have a long journey, two months walking straight every day, and I felt that was the biggest achievement for me.

“My biggest challenge is I need help. A tent is very uncomfortable without arms. Buttons, clothing, anything practical, taking off the prosthesis then you want to go to the toilet and you have to wake up your teammates and say ‘hello, help’.

“The mountain climbing was good because me and my sherpa were well co-ordinated so we found solutions. But in the tent it is a struggle.”

Dancing in front of a TV audience was a challenge of a different kind.

“It was a programme called Shall We Dance? I got to the fourth programme and did three dances but I was struggling. I felt the pressure very much and was too nervous, but it was great fun.”

Pedersen is Norway’s Chef de Mission for the Beijing 2022 Paralympic Winter Games, a role he has filled at every edition since Beijing 2008.

It has been an amazing journey, which began at the age of 14 when he thought it would be a good idea to climb a live electric pole. A 17,000-volt charge surged through him. His arms had to be amputated.

“As a farmer this was a disaster,” admitted Pedersen, who had been lined up to take over from his grandfather on the family farm.

“But soon I was quite positive about being without the most important thing for farming – my arms – and I started with sport.

“Everything was different in the world of sport. Outside it was so negative. It was about what I couldn’t do but sport was about what I could do, how I could improve.”

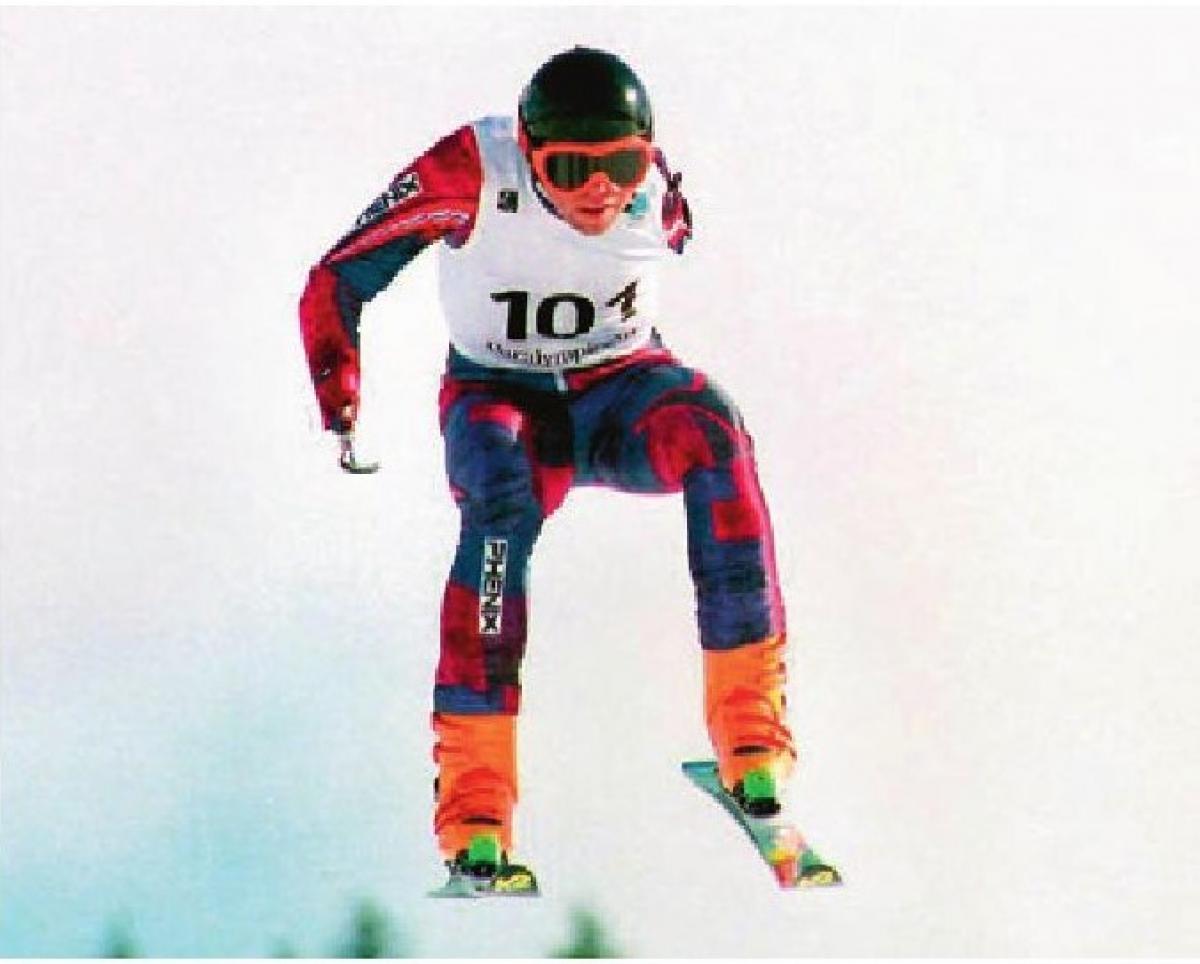

Pedersen tried table tennis and swimming but decided he liked track and field and alpine skiing best. In 1980, he won four gold medals at Arnhem (100m, 400m, 1500m, long jump) and in the same year won three gold at winter Games in Geilo (slalom, 10km and giant slalom).

In 1984, he took the 1500m and 5000m titles in the Stoke Mandeville/New York Games and competed at Innsbruck. Four years later, again at Innsbruck, he took gold in giant slalom and downhill and called it a day.

Then Lillehammer was awarded the 1994 edition and Pedersen was asked to change his mind.

“I had quit. It was hard, the only thing I did was practise and I was very dedicated so it was difficult for my family life, especially when my wife (Martha) fell pregnant when we had been told we could not have children, and our daughter Erica was born in 1987.

“But I came back and Lillehammer was amazing. It was a huge positive experience for me – aiming to be the best country and doing my part.”

Pedersen took the super-G and giant slalom gold medals at Lillehammer to complete his tally of 13 but it is his silver in the downhill which he remembers the most.

“I made a mistake. I had to do something right and I didn’t. It was into the steep part, you have to set up the line to be not too late. I was 0.3 seconds too late. I was kind of happy with that silver and it was good for my friend in Germany (Gerd Schoenfelder) that he won the gold.

“Mistakes are what you learn from and I remember it so well.”

Pedersen, who also competed in sailing at Sydney 2000, has had his name given to a rehabilitation hospital in Norway – The Cato Centre – for people with illness or who have had accidents. His profile remains high.

“When I am at a dance or a bar, people come to talk to me but it is very positive. I am lucky that people still remember me.”