A personal look back at 25 years of the IPC

After working for the IPC for 25 years, Leen Coudenys, IPC Governing Board Executive Assistant, is the organisation’s longest serving employee and knows the organisation better than most 22 Sep 2014

IPC Governing Board Executive Assistant Leen Coudenys is the IPC’s longest serving employee.

When you look at the original objectives for the creation of the IPC, we certainly have achieved a lot when it comes to turning the focus on sport versus disability.

On Monday 22 September, the International Paralympic Committee (IPC) celebrates its silver jubilee following its formation in Dusseldorf, Germany, in 1989.

One person who joined the IPC immediately after that famous meeting 25 years ago, and who still works for the IPC today, is Leen Coudenys, IPC Governing Board Executive Assistant.

Paralympic.org caught up with her to find out her views on how the organisation has changed over the last quarter of a century.

Paralympic.org: How did you get involved?

Leen Coudenys: I got involved with the ‘Flemish League for sports for athlete with a disability’ and volunteered at a wheelchair basketball competition.

In November 1989, the very first meeting of the Executive Committee took place in my hometown in Bruges and I helped out with the logistics of it and with taking the minutes.

What mattered to me in 1989 was overcoming a personal loss and finding a new meaning in life. The Paralympic Movement showed me the way, i.e., to focus on what you have rather than on what you lost; basically the same as for many Paralympic athletes.

When the IPC was formed 25 years ago, did you ever believe it would grow to the size it is today?

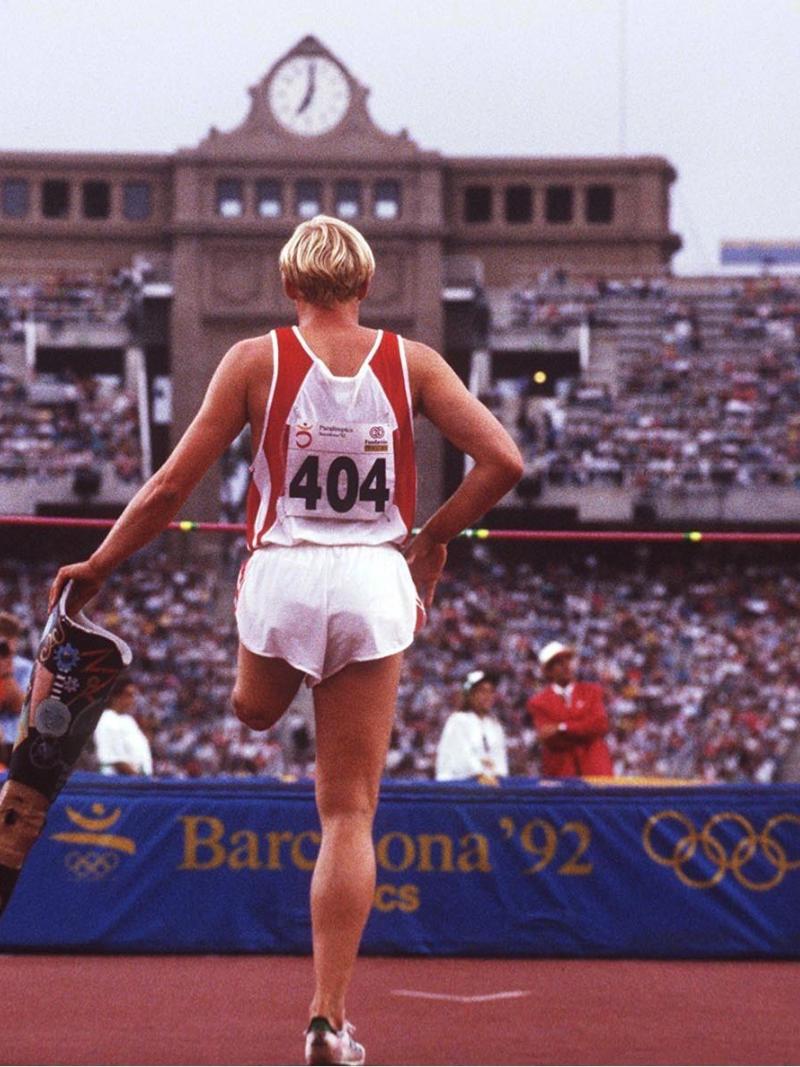

No, how could I? Back in 1989 I had no experience. For me at that time, engaging with the Paralympic Movement seemed the right direction to take because I believed in the values it represented. I had no clue what the IPC’s destination would be. The 1992 Games in Barcelona however, were an eye-opener to me. They had a real ‘wow’ effect! Only then did I see the potential of the Games, how it could effectively change perceptions and change society for the better.

What was the hardest part about starting a new organisation?

The lack of resources was definitely the number one concern.

There was no money for professional staff. All elected officers and sports chairpersons were also the ‘working force’. There was also no money to travel to meetings; either the persons themselves or the body that had nominated them paid for all expenses.

The IPC administration was supported by the ‘Flemish League for Sport for People with a disability’, which offered working space and equipment.

There were a couple of key challenges to address in the first two years. First of all the IPC had to agree with the International Co-ordinating Committee (ICC) on the handover of responsibilities and solve the dispute about who would be responsible for the 1992 Games in Tignes and Barcelona.

The IOC President, Juan Antonio Samaranch, put it as a condition for the ICC and IPC to agree on this point before the IOC would provide any financial support to the Movement. We also had to settle a dispute with the IOC over the use of the IPC logo (five tae-guks), which the IOC thought was too confusingly similar with the five rings, and developing the IPC trademarks was much needed to be able register the IPC and create a marketing programme.

A lot of energy needed to be put into the set-up of the governance structures and especially the sport specific technical structures that needed to combine the expertise of the various impairment groups. There was a lot of controversy around the development of the first functional classification systems to underpin the new sport specific approach.

In hindsight, if you could change anything from the last 25 years what would it be?

I find this a difficult question. Every step, every decision, along the way shaped the IPC as it is today. And yes, mistakes were perhaps made but decisions were taken based on the knowledge of that moment and within the resources available at that time.

There were many and strong differences in opinions. Often it was difficult to find consensus but there was one thing all officers had in common, i.e., the best interest of the athletes and a huge commitment. If there’s one thing I would have wanted to be different, it’s finding a better way to keep all those highly committed volunteers on board and continue to gain from their expertise.

Personally, what has been your favourite moment from the last 25 years?

I was given the honour of unveiling the new IPC logo during the closing ceremony of the Athens 2004 Paralympic Games. Having been so much involved in the creation of the old logo I was particularly proud to stand there in the middle of the stadium unrolling the flag with the Agitos while the IPC hymn was playing.

It was both symbolic and emotional for me; the organisation that I had known from ‘standing in its baby shoes’ had now matured. I still consider that moment as an absolute highlight in my life. Standing there in the middle of that stadium that was packed with people, I was given a glimpse of the pride and excitement an athlete must feel when receiving his/her medal.

What do you feel has been the most important moment in Paralympic history so far?

The signing of the first agreement with the IOC gave us the guarantee that the Paralympic Games would be held in the same city of the Olympic Games and with the same level of services as for the Olympic athletes. That was like a quantum leap for the IPC and we are still building on it today.

Where do you feel the Paralympic Movement can go from here?

When you look at the original objectives for the creation of the IPC, we certainly have achieved a lot when it comes to turning the focus on sport versus disability. The Games have changed people’s perceptions; there is also more understanding and more appreciation for the hard work and achievements of the athletes. We have come a very long way but there is still a long way to go. We have not reached all parts of the world; there is still a lot of grassroots development needed. The IPC can only continue to be strong if that work is well undertaken. At the same time we will need to look into how new technologies will impact on the life and performances of athletes and then ensure that these technologies can become available to all. Infrastructures and services are good in the more ‘sophisticated’ cities or communities around the world but a lot remains to be done in other parts; and that counts also for those countries where para- sport is perceived as already being well developed.